Follow a Local Wildlife Site through the system - Part I

Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) form an important part of the protected landscape in the UK. NEYEDC has a crucial role in collecting, processing and distributing LWS data within North and East Yorkshire, as do many Local Environmental Record Centres within their own districts.

LWS are an important consideration in local planning and thus many of our clients require access to this data to support ecological work out in the field. Although frequently encountered in the sector, following a number of iterations in recent years, Local Wildlife Sites can be a source of confusion. During this blog piece I will account what I have learnt as I break down the Local Wildlife Site system and follow a site through from survey to panel decision. In Part I of this series we will discuss the background of LWS and look at the work involved in the preparation and survey of a LWS in Scarborough, Burton Riggs.

But first of all, what is a LWS?

Local Wildlife Sites can be broadly described as parcels of land with substantive value for local conservation. However, each Local Authority (LA) defines LWS slightly differently, even with different names, you might of heard of them as SINCs, County Wildlife Sites, Sites of Special Interest and many more... But the clear commonality between these sites is they are all local; in that they are defined locally and impact local planning, unlike national or international sites (such as Ramsar Sites or AONBs) which have higher protection by law and are recognised nationally and/or internationally. They are also known as non-statutory sites. Unlike other protected sites, LWS designation does not demand any particular actions from the Landowner and does not give the public rights of access. However, many local wildlife sites are publicly accessible, such as the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust owned site, Burton Riggs, which will be looking at here.

Site Designation tiers within the UK can be split into three groups; local, national and international. Special Areas for Conservation (SACs) and Special Protected Areas (SPAs) are sites protected by the European Union Habitats Directive whilst Ramsar sites are wetland sites protected internationally. At the other end of the spectrum we have our Local Wildlife Sites (LWS).

LWS hope to serve an important purpose in terms of connecting protected, quality pieces of habitat, to provide corridors or steppingstones, for biodiversity. These are especially important within the highly fragmented landscape of the UK, where many species face declines due to competing land uses.

And where did they come from?

The designation of these sites arose following systematic Phase 1 Surveying of each of the districts of North and East Yorkshire (and across the UK), within the period of 1988 to 1993. The habitat data provided by these surveys allowed for the first thorough identification of a series of non-statutory sites deemed important for conservation on a local level. These sites would go on to become LWS.

Once a need to identify these locally important sites was established, local authorities across the country set about devising concrete guidelines to determine which sites were suitable for this new designation. It was agreed that each region would create their own criteria, in order to reflect specific local biodiversity priorities. The development of each of these systems independently explains the variety of names that LWS are described as (SINCs in North Yorkshire and LWS in East). Whilst designing a custom system that reflected the individual needs of each geographic region was important, a lack of guidance meant there were disparities in the quality of different LWS processes. Following the release of guidelines published by DEFRA in 2000, many LWS systems were reimagined, and the new unifying term ‘LWS’ was suggested to replace prior synonyms. Some systems required little changing, for example the rigorous design of North Yorkshire’s system was presented as a template to other local authorities. The result of these developments is the LWS we see today, although the guidelines are unified and standardised, making them similar between regions, they are not identical. For example species criteria tend to be quite different between regions, depending on the unique geography, biodiversity and pressures of each county. Other new criteria may also be added depending on the interests and expertise of those working in the region, such as the Verge Criteria in East Riding, which allows some of East Riding’s Verge Nature Reserves to be designated as Local Wildlife Sites.

Example Site: Burton Riggs

To maintain an accurate list of all the LWS in an area, both existing sites and potential new sites (candidate sites) must be surveyed. Resurvey of existing sites tends to be done on a 10-year basis, with a review of which sites need to be surveyed happening every year. To maximise resources, a site must be deemed appropriate by the panel before it is put forward for survey, at which point it may be granted Candidate LWS (cLWS) status. This step also ensures that any sites submitted which lack a factual basis can be sieved out, which is important as cLWS hold some standing in planning. Following a professional survey, the panel will assess a site using the Site Selection guidelines to determine if it meets the LWS standard (either for the first time or as part of the resurvey). There are a range of attributes a site may have in order to be granted LWS designation, these include, rarity, size, diversity, naturalness and representativeness, which are regularly updates and assessed to ensure they are fit for purpose.

This infographic shows a simplified version of the LWS process. Each dotted arrow represents a step in the process where the panel must make a decision and a site may be deleted, deferred or accepted at each of these points.

There are two crucial barriers to reaching the survey step in the process:

Availability of funding and resources – professional surveyors are expensive and funding must be secured to ensure that the surveys can actually take place. In the case of North and East Yorkshire, NEYEDC are responsible for the management and dissemination of the data as well as organising of the surveys, which must be funded as well.

Landowner permission – the majority of LWS can be found on private land therefore if the landowner refuses access to the land the survey cannot go ahead. Despite site designation landowners remain in control of both the management and access, as it is still their land. Unfortunately, there can be some confusion amongst landowners about how their rights may be impacted by LWS designation, which can be an off-putting factor to many. Other factors such as historical disputes between environmental bodies and landowners as well as pressure from neighbouring landowners can reduce the chances of gaining permission from some landowners.

Burton Riggs local wildlife site had previously met the Site Selection guidelines for mixed habitat and presence of great crested newts.

Important marginal vegetation such as the Purple Loosestrife, Crosswort and Water Mint pictured above will be noted by the surveyor as a Target Note.

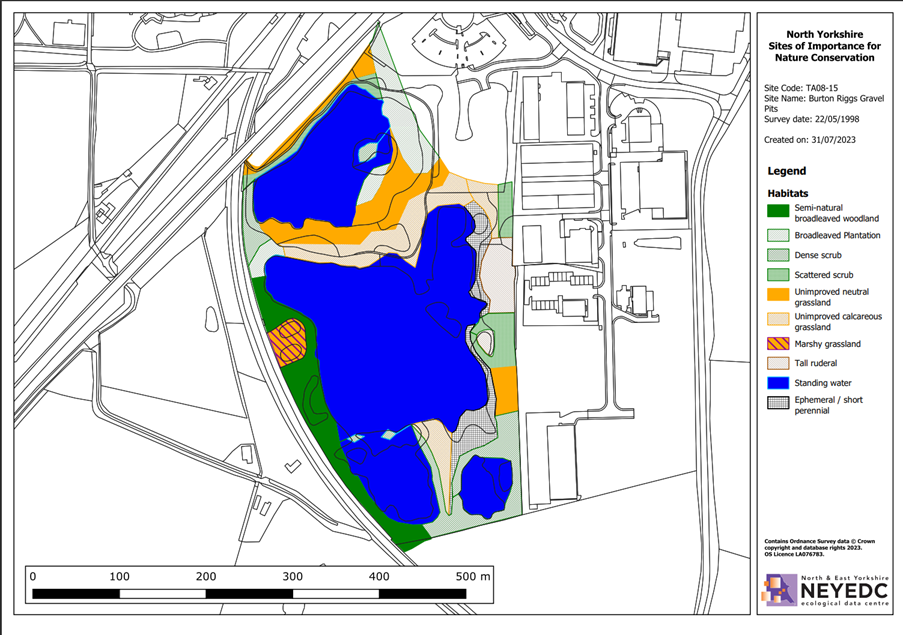

The habitat map of the Burton Riggs site created as part of the 1998 Survey Report

Surveying the site

In the Burton Riggs example, landowner permission was easy to obtain as the site is owned by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust. In addition, funding was available, and so the survey process could be carried out. Burton Riggs was designated a LWS back in 1998, and this was the last time the site had been surveyed, thus was well overdue a resurvey.

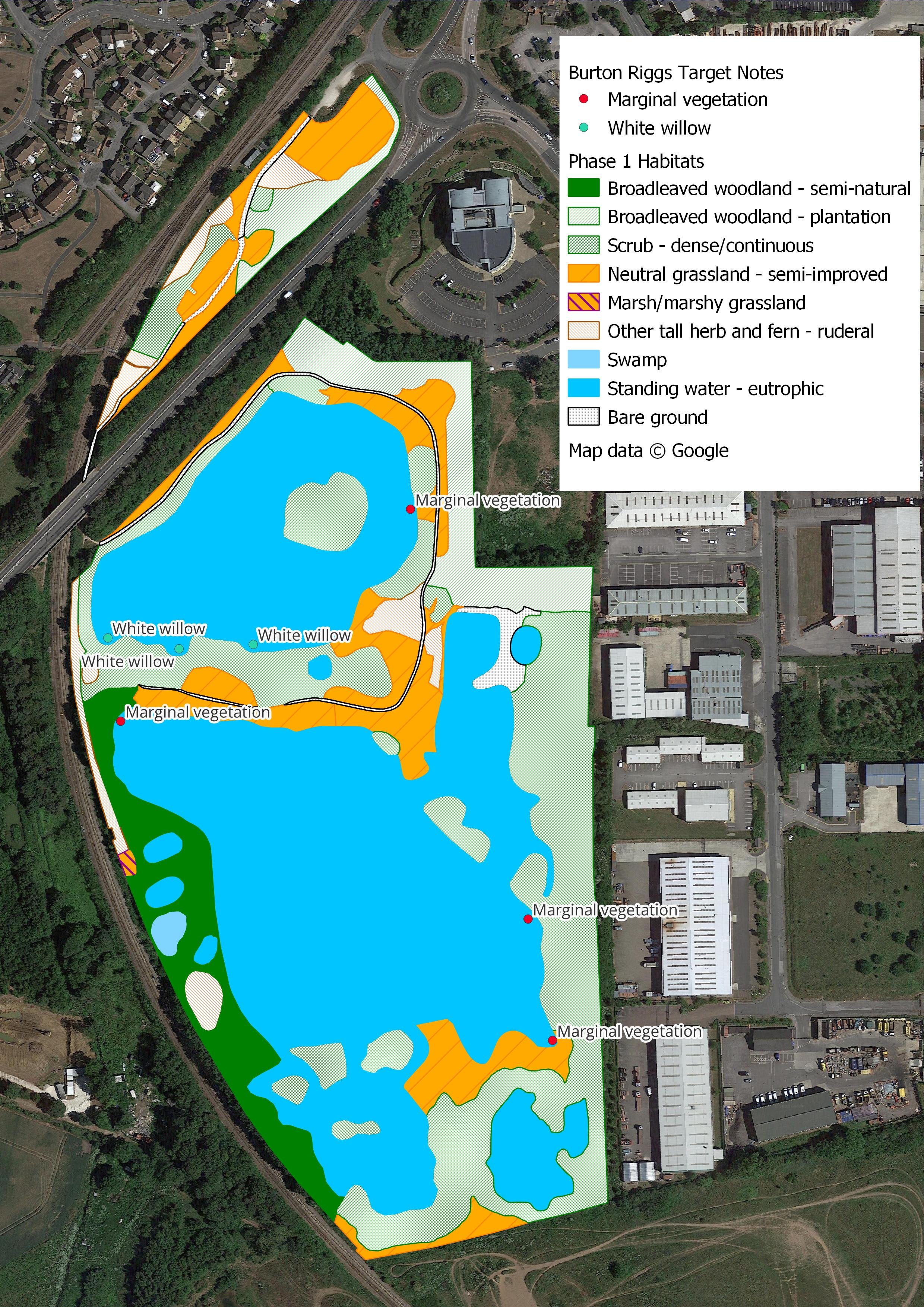

A rough map is often drawn out in the field before fine tuning by the surveyor

Using details from previous survey reports, (habitat maps and species lists), aerial photographs and maps, the surveyor will complete the survey report. The surveyor is required to map habitats across the site using Phase 1 surveying methods, with note of any National Vegetation Communities (NVC) of particular importance, and to create a species list of all species found on the site (which tends to focus on botanical species). They will also write a site description and add comments about both current and suggested land management ideas for the site, potential threats, amenity uses and other habitat features.

There are a number of difficulties faced when surveying a site that may impact the accuracy and comparability of information collected in a survey report. There may be problems with the accessibility, such as lack of access provided by physical barriers, for example very dense scrub or steep banks. Another key factor, is the time of year that a survey may have taken place. For instance, the initial Burton Riggs survey was completed in May 1998, whereas this year the survey was completed last August. Crucial seasonal differences can be seen in the species lists, such as the presence of a variety of orchids during May, and not this time around during August. Other difficult weather conditions, such an early heat wave in Spring, meant that surveying earlier in the year would not have been an accurate representation of the site either, as many plants had been burnt and killed in the extreme weather.

Post survey analysis

Creating an accurate habitat map can be difficult, especially when using manual techniques such as drawing boundaries and details onto a paper map, which is one of the difficulties we try to minimise in the post survey analysis. For example, surveyors are thought to hugely overestimate the area of a steep slope when mapping, as it can be difficult whilst on the ground to interpret the three-dimensional aspects of the land into a two-dimensional birds-eye view of the land. To minimise issues of spatial inaccuracy, boundaries are matched to MasterMap, a seamless spatially accurate database of all fixed features found across the UK. Comparison of old maps, MasterMap and aerial photography help to interpret the surveyor’s paper map to the highest possible digital accuracy.

When digitising habitat maps, all boundaries are snapped to MasterMap and should be carefully snapped to each other to create a seamless layer with no gaps (the picture shows a segment of habitat prior to editing)

Part-way through the digitisation of the surveyor’s map using qGIS

The final map, complete with Target Notes and Phase 1 styling.

Scoring

The next step is to analyse the species list with respect to the LWS scoring guidelines. We can see that previously, this site gained LWS designation for a number of reasons, including high scoring on these two guidelines:

Presence of Great Crested Newts

Mixed Habitat

This introduces us to the Species Criteria and the Habitat Criteria, which are the two ways by which a site may be designated. As the survey conducted was a Phase 1 Habitat Survey, only the Habitat Criteria can be assessed. Note that a species-specific survey would need to be completed to examine Great Crested Newts species criteria. The next step in the post survey analysis will be to plug our species list into the Scoring Calculator, to find out whether the site scores highly enough for each habitat type. We’ll take a closer look at the scoring system, and the post-survey scores next time…

Stay tuned to delve into the Site Selection guidelines in more detail. A step inside the LWS Panel will enable us to see if our Burton Riggs site has maintained its status as a LWS or not…