Bark to Basics: Updating Yorkshire's Ancient Woodland Inventory

Our Ancient Woodland Inventory Project Officer, Robin, aided by our new Ecological Data Officer Josie, have been taking on the huge task of updating the Ancient Woodland Inventory in our region.

What are Ancient Woodlands?

Ancient woodland is defined as an area which has been continuously wooded since at least 1600CE in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and since 1750 in Scotland.

“Continuously wooded” does not necessarily mean the area had a continuous cover of trees and shrubs over the whole site or time frame, however. Alongside the woodlands themselves, open spaces and other habitats such as moors, heath, arable, glades, and linear features such as historic tracks, ponds and streams that flow through the site are usually included in the ancient woodland sites to maintain habitat cohesion.

An example of Ancient Woodland and some of its distinctive ground flora at Burton Bushes, East Riding of Yorkshire. Photo credit: Clare Langrick.

The original Ancient Woodland Inventory (AWI) was compiled by the National Conservancy Council (NCC) between 1981 and 1992 as a ‘site-by-site listing of probable ancient woods’ (Spencer & Kirby, 1992). The aim was to create a better information source for the distribution and size of ancient woodlands as a resource at a time when it was starting to be acknowledged as an important and irreplaceable biological and cultural asset. The original AWI was paper based, with maps and reports produced on a county-by-county basis. It was digitised in the 1990s in order to create a National dataset which is currently managed by the NCC’s successor, Natural England.

The AWI and subsequent studies, such as the initial work on ancient woodlands carried out by the ecologist Oliver Rackham in 1980 and later by Spencer and Kirby (1992), have shown ancient woodlands are more ecologically diverse and so have a higher nature conservation value than more recently established woodlands. This makes them invaluable habitats worth identifying and protecting.

Alongside veteran and ancient trees, ancient woods can have distinctive ground flora (with species such as bluebell, wood anemone, golden saxifrage, ransoms and wood sorrel) that can act as an indicator of current or former ancient woodland at a site.

Ancient woodlands roughly fall into two categories:

Ancient semi-natural woodland (ASNW)

These wooded sites are mostly composed of trees and shrubs that are native to the site and have not obviously originated from planting. However, it is not always simple and there may be instances of ASNW where woodlands containing small pockets of planted native trees that can be included. These small stands or pockets may have been planted in the past for coppicing or pollarding and the tree or shrub layer may have matured and established by natural regeneration.Plantations on Ancient\woodland Sites (PAWS)

These are areas of Ancient Woodland that have been felled and replaced by planted trees that are not necessarily native to the site, such as Norway spruce and non-native broadleaves such as sweet chestnut. PAWS sites often retain features evident of their former Ancient Woodland status, such as soil composition, ground flora, fungi species and even woodland archaeology. These sites often respond well to restoration management projects.

Both ASNW and PAWS sites are classed as Ancient Woodland and are allowed equal protections as outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Wood Pasture and Parkland

In addition to PAWS and ASNW, wood pasture habitats will now be included in the AWI. The Woodland Trust describe wood pasture and parkland as “land that has been managed through grazing. They can be ancient, or of more recent origin, and occur in regions with distinct woodland types, such as Caledonian forest. Some started as medieval hunting forests or wooded commons, and others are the designed landscapes from large estates. They are often perfect for spotting ancient and veteran trees.”

These sites, including some parkland, upland grazed woods, Royal Forests and registered Parks and Gardens, often have only sporadic populations of veteran trees and were not incorporated into previous iterations of the AWI due to the low density of trees present. However, these are important habitats and will be identified for inclusion as part of this AWI update as they should be awarded the same protections as the other forms of ancient woodland.

Updating the Ancient Woodland Inventory in North and East Yorkshire

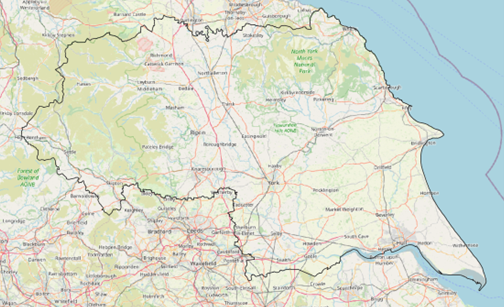

Here at NEYEDC we cover a pretty big area (approximately 11,000km²). From the Lancashire/ Cumbria borders in the west, to Northumberland in the north, down to West and South Yorkshire and across to the rugged and rapidly changing North Yorkshire and Holderness Coastlines in the east, the diverse nature of our geography incorporates forests, dales, uplands, lowlands, mountains, moors, meres & mires, villages, market towns and cities (to name but a few) and includes some Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB’s). We are very lucky to have all this variety in our region, despite the extra challenge it brings to large projects such as the AWI update.

The NEYEDC area shown by the black line superimposed onto OpenStreetMap (OSM).

The current AWI update

Since its creation and subsequent digitisation, the AWI has been used for a range of processes in planning, nature conservation, ecological research, and forest management for which it was not initially designed. With increasing developments in technology (e.g. aerial photography) and mapping systems, there is a much larger and more accurate evidence base now available for us to use to improve this very important resource. The updated version of the AWI will also differ from the limitations of the previous paper and digitised versions as the minimum capture size for woodlands has dropped from 2 to 0.25 hectares in order to incorporate smaller, but still significant, pockets of ancient woodland.

The current update to the AWI is split into distinct phases. The first phase involves the capture of a long-established woodland (LEW) layer by comparing historic maps to recent aerial photography. This LEW layer includes both woodland that is pre-1600 as well as woods which are post-1600 but originate before the “Epoch 1” Ordnance Survey maps of the 1850s (see below). Once this initial phase is complete, the newly constructed LEW layer is compared against the most recent version of the AWI to identify the new areas of ancient woodland. In this stage, the long-established woodland polygons are classified according to a number of key categories to help us judge which need further investigation.

After this identification phase is complete, we move onto the evidence gathering and integration stage. Whilst the earlier phases have built up a dataset, the next phase allows gaps in the evidence to be filled and ultimately for the fine tuning of woodland sites to begin. The evidence used in this phase includes investigating further (and often older) historic map resources, as well as site surveys in order to “ground truth” the nature of the trees, shrubs, ground flora alongside landscape and possibly archaeological features at some sites. After this, all the sites are checked before a final version of the data is sent back to Natural England (along with a rather extensive Summary Report).

The AWI update process: In the beginning there was…a blank map

The NEYEDC area was split into 5km² tiles (507 of them to be precise) to enable a systematic mapping approach.

After first separating the area of Nidderdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) as a separate mapping project, which was initially carried out separately by a delivery partner in order to manage the workload*, we then mapped some tiles from around the North and East Yorkshire area to get a feel for the different geography types and gain experience with the Phase 1 mapping process.

After mapping these initial “trial tiles”, we shifted the focus onto key wooded areas (including the woodlands of the North Yorkshire Forest Park), next the North Yorkshire area was mapped systematically going West to East along with the East Riding of Yorkshire following the same pattern.

*Nidderdale AONB was then remapped by ourselves at a later date.

Phase 1: the creation of a Long-Established Woodland (LEW) layer

Phase 1 involves the base mapping of woodlands that were present around the time of publication of the first series of Ordnance Survey maps (what are called the “Epoch 1” maps from around the 1850’s) and are still present today, this is known as “long-established” woodland (LEW). This provides a basis for identifying woodlands with history reaching all the way back to the 1600CE and earlier. The approach for carrying out Phase 1 is based around the comparison of woodland sites present on these historic maps with recent aerial photographs.

Historic maps

1:2500 scale (25 inches to the mile) maps were recommended for this project, but coverage is poor as much of Yorkshire (and Northern England in general) wasn’t mapped at this scale until the late 1800’s. Instead, 1:10560 (6 inch to the mile) maps were used, and later “Epoch 2” (1: 2500 maps from the late 1800’s) used as a backup evidence base to corroborate the earlier maps (where they were available). Some caveats remain with this latest version of the AWI, and the sometimes patchy and incomplete nature of some of the historic maps means the information is based on the best available evidence and is ultimately subject to review.

The Phase 1 process

We start with a complete Ordnance Survey Mastermap layer (a topographic editable GIS layer supplied by Natural England). This layer contains an attribute table which will be modified as the AWI update process goes on. The initial Mastermap file supplied covered the whole of England and was very unwieldy so had to be split first into the NEYEDC area and then into smaller 20km2 blocks in order to be split further into more manageable 5km2 tiles in order to be worked on (see the map above).

This Mastermap was then laid over both the “Epoch 1” OS maps and modern aerial photography to allow identification of woodland present both now and historically. At this stage, a series of codes were used to classify wooded regions based on whether woodland or woodland pasture was present in both map eras. We were also able to identify parts of the map that may need editing to properly reflect the historic woodland distribution.

Once the mapping of the long-established woodland (LEW) in North Yorkshire was completed* we created a LEW layer for each of the North Yorkshire Districts, the City of York, and the East Riding of Yorkshire (including the City of Hull).

Map showing an early version of the long-established woodland (LEW) layer for North and East Yorkshire, indicated by the grey polygons.

Phase 2: Analysing the LEW LAyer

The aims of Phase 2 are to quality check and further investigate the newly generated dataset using various outputs from the Phase 1 LEW layer and comparing it to the existing AWI. We want to find:

Any areas of land included on the current AWI but not assessed as woodland in Phase 1 –these could be “Mapping Errors” (where there is no woodland at all) or “Designation Queries” (where there is woodland but it is likely to be from after the 1850’s). Large sites in these categories will require re-assessing.

Areas identified as Previously Designated Ancient Woodland – areas of long-established woodland that are already included on the current AWI.

Any Potentially New Ancient Woodland– significant areas of long-established woodland that are not included on the current AWI.

Insignificant areas of land (known as “slivers”) that represent differences in mapping precision between the two datasets. These small slivers will be removed from the data set.

When this is done, we have an updated set of layers that tell us which of the above categories each long-established wood falls into, which will help us decide what further investigation is needed to find out if it truly meets the criteria to be an ancient woodland.

The beautiful Burton Bushes again, in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Photo credit: Clare Langrick.

What comes next?

Phase 3 is all about further investigating the Potential Ancient Woodland we have identified so far. This will include research in historical archives (such as tithe and estate maps) housed at dedicated regional archive centres used in conjunction with a series of ground surveys carried out with specialist ecological surveyors. This combination of invaluable local records and on-the-ground ecology expertise will allow us to determine the true nature of these potential Ancient Woodland sites.

We can’t wait to get stuck in! We will provide more updates about Yorkshire’s ancient woodlands in future (hopefully including pictures of some very pretty maps and even prettier woodlands).